If Once Upon a Time in the West were any slower, it would be classified as a still life. But therein lies its brilliance—Sergio Leone’s 1968 masterpiece isn’t just a Western, it’s a grand, operatic elegy to the entire genre. It takes every trope, every dusty cliché, and stretches them to their breaking point, transforming what should be a simple tale of revenge into something mythic, something almost supernatural in its grandeur.

From the very first scene, Leone sets the tone with a ten-minute symphony of silence. Three gunmen, waiting at a train station, doing nothing except letting time breathe. Water drips. A fly buzzes. A windmill creaks. Not a word is spoken, and yet, the tension is thicker than the dust swirling in the air. And then—Harmonica arrives.

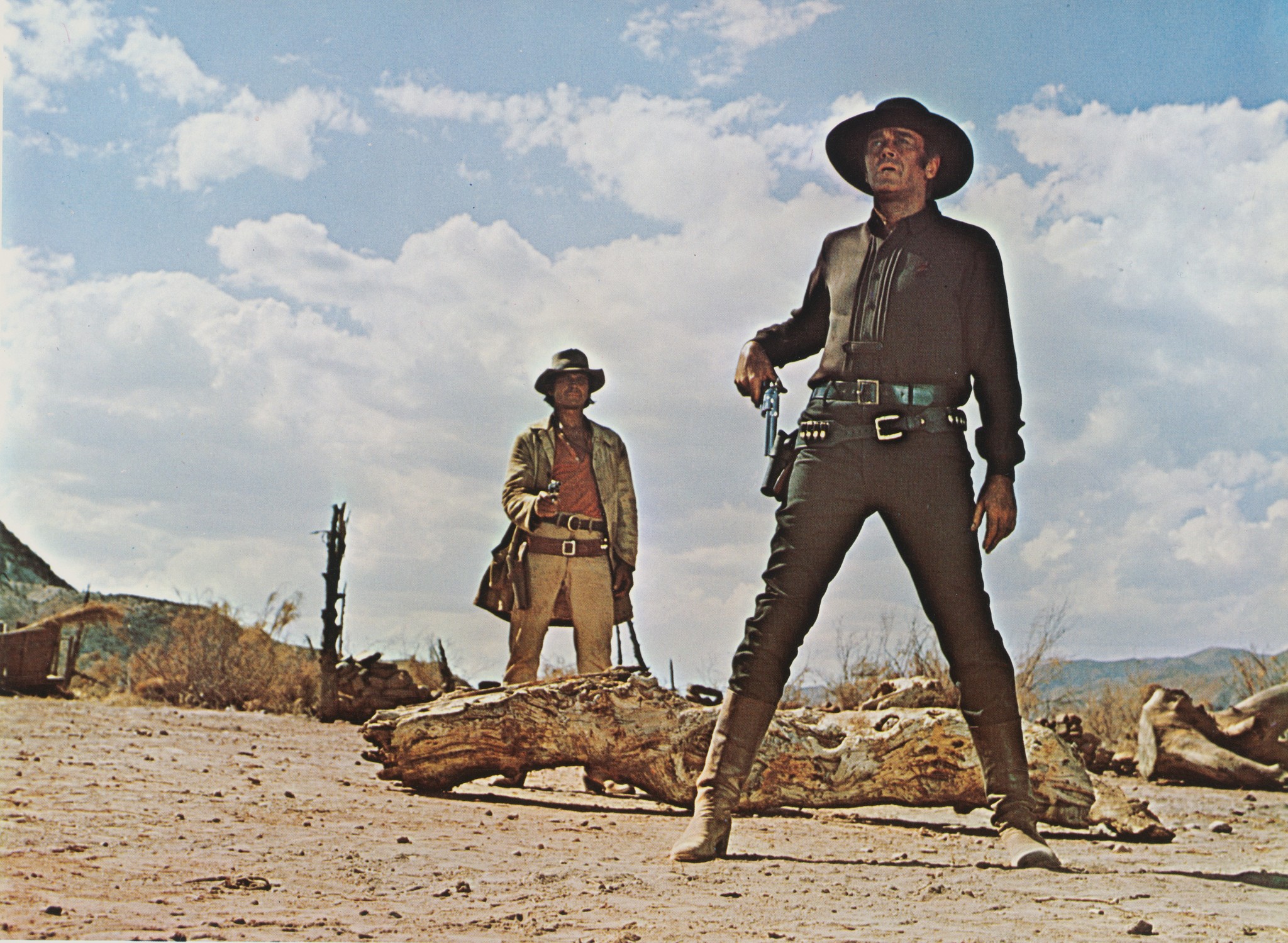

Charles Bronson, the man of granite, plays the mysterious Harmonica with the expressiveness of a stone carving, which is to say, he is magnificent. He speaks in monosyllables, kills with precision, and carries a haunted melody that tells you all you need to know about his past. His foil? Frank, played by Henry Fonda, who abandons his usual twinkle-eyed decency to become a remorseless killer so chillingly casual in his evil that it makes your blood run cold. When Fonda shoots a child in cold blood within the first fifteen minutes, you realize Leone isn’t here to play cowboys and Indians—he’s here to bury the Old West six feet under.

Then there’s Claudia Cardinale as Jill McBain, the heart of the film and perhaps the only character with a soul uncorrupted by revenge. A widow trying to stake her claim in a brutal world, Jill isn’t just a love interest or a damsel—she’s the beating heart around which all these violent men orbit, and Cardinale plays her with a depth rarely afforded to women in Westerns.

Leone’s direction is indulgent, excessive, and utterly perfect. Every frame is composed with the precision of a Renaissance painting. Close-ups so tight you can count the pores on Bronson’s face. Wide shots so expansive they make the desert look like an alien landscape. And let’s not forget Ennio Morricone’s score—dear god, the score! Morricone doesn’t just write music; he weaves spells. Each character has their own theme, their own haunting motif, and the music tells you more about them than dialogue ever could. The final showdown between Harmonica and Frank, set to Morricone’s aching strings, is one of the most emotionally charged duels ever put to film.

But Once Upon a Time in the West isn’t for the impatient. It’s long. Very long. It luxuriates in silence, in stolen glances, in the weight of history pressing down on its characters. Leone doesn’t rush—he savors. Every gunfight is a slow boil, every stare-down a meditation on fate.

Would I recommend it? Without hesitation. It’s not just one of the greatest Westerns ever made; it’s one of the greatest films, period. Once Upon a Time in the West is a requiem, a lament, a cinematic monument to an era that was already vanishing when the film was made. It’s violent, poetic, operatic, and undeniably grand.

Rating: 5 monocles out of 5

For Leone’s masterful direction, Morricone’s legendary score, and the sheer operatic beauty of watching the Old West fade into legend. If you only watch one Western in your life, make it this one.